The different realities of education in colonial Kerala

Editorial / November 02, 2024

The common belief that an educated child is automatically a "good" child is not as universal or timeless as it seems. This connection between childhood and education has developed over centuries, influenced by changing social norms, practices, and ideas. Various fields—such as medicine, philosophy, literature, and law—have significantly shaped our current understanding of childhood as a distinct phase marked by unique physical, mental, and intellectual growth.

In modern southern India, particularly among middle-class families, perceptions of childhood have transformed dramatically. Factors like the reduction of child labour, smaller family sizes, decreasing fertility rates, and a growing emphasis on formal education have all played a role in this shift. Sociologist Viviana Zelizer introduced the term "emotionally priceless" to illustrate this change: children, once seen primarily as economic contributors, are now valued for their emotional significance. This evolution, beginning in the mid-20th century, reflects broader global trends, particularly in Europe and the United States, where education is increasingly viewed as an investment in a child's emotional and intellectual development rather than just a practical necessity.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, it often served as a means of social control, aimed at regulating behaviours, instilling discipline, and fostering social cohesion. Various reform movements, religious missions, and state initiatives promoted education to combat poverty and cultivate responsible citizens. Over time, formal schooling became central to the concept of childhood, reinforced by compulsory education laws that framed this period as one of extended learning and moral growth. The state began to adopt a quasi-parental role in this context.

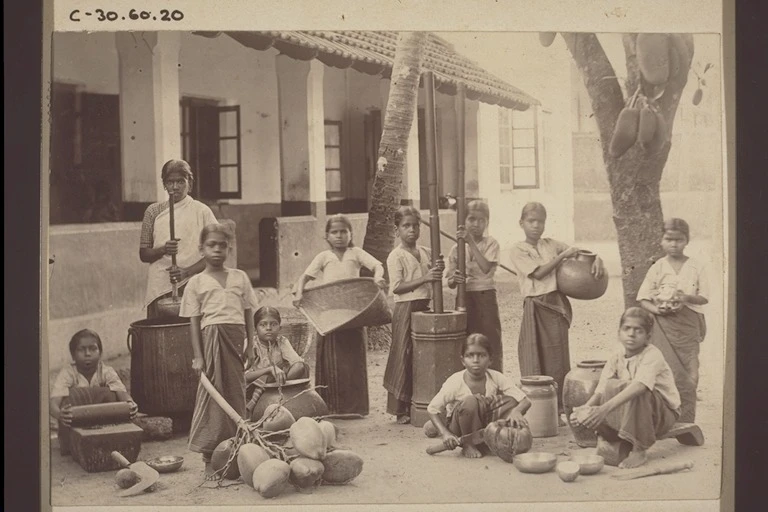

In colonial India, childhood experiences varied significantly based on caste and class. Upper-caste and middle-class families embraced the idea of childhood as a protected and innocent stage, while children from labouring, low-caste backgrounds faced starkly different realities. These children were often viewed with pity, subjected to strict control, and denied the same educational opportunities enjoyed by their upper-caste peers. Their caste status frequently led to perceptions of their childhoods as "failures," with many seen as "beasts of burden," excluded from formal schooling and reliant on state welfare.

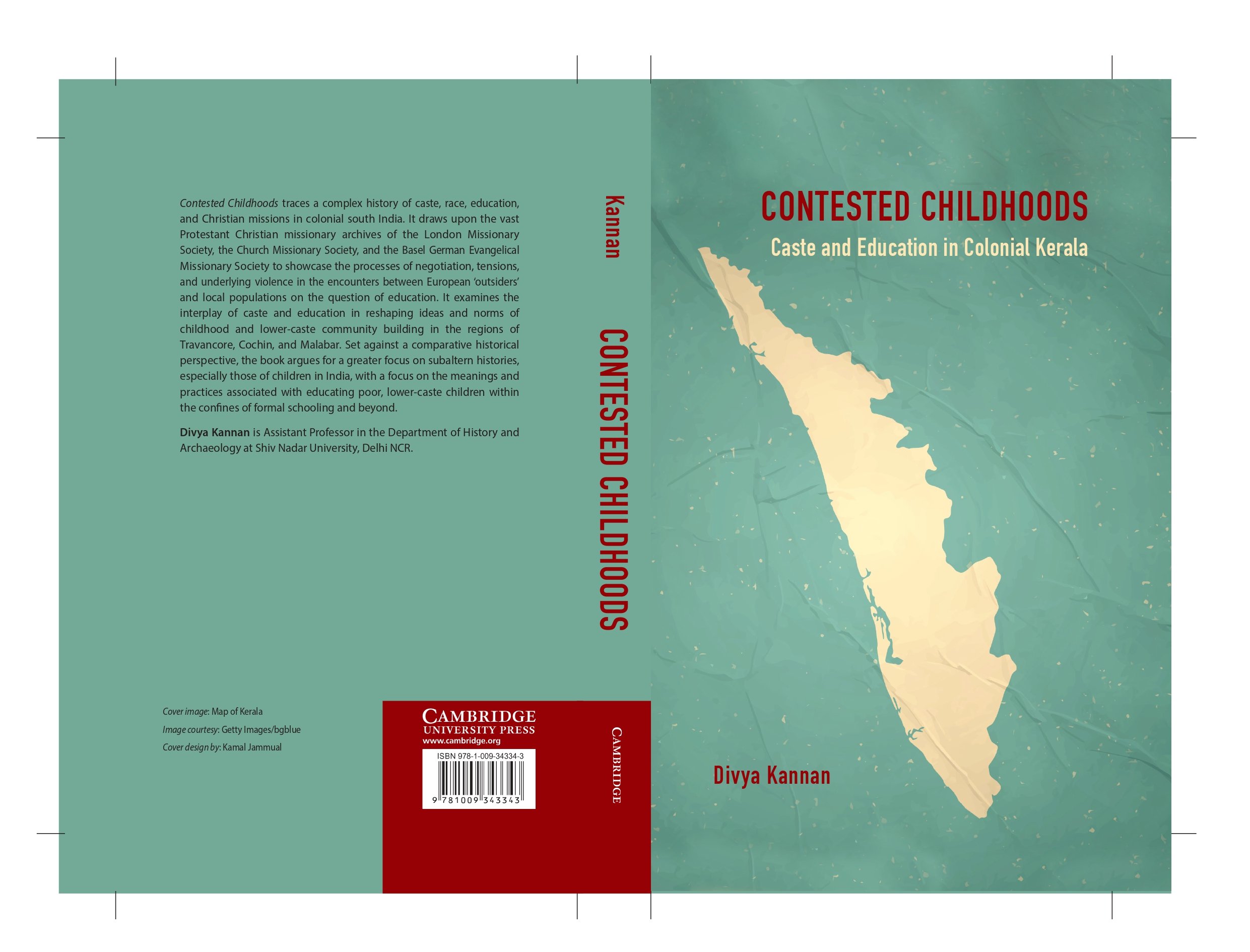

The book Contested Childhoods: Caste and Education in Colonial Kerala (Cambridge University Press, 2024) by Dr. Divya Kannan, Assistant Professor, Department of History and Archaeology, critically explores the intertwined histories of education and childhood in the princely states of Travancore and Cochin, as well as in British-ruled Malabar. It foregrounds the tensions between the idealised notion of childhood as a protected time for learning and the harsh realities faced by marginalised children who were often relegated to separate educational spaces. The role of European Protestant missionaries in shaping educational opportunities for impoverished children in Kerala is central to this narrative.

Missionary schools, such as those run by the Basel Mission in Malabar, positioned themselves as providing a "home away from home" for destitute and orphaned children. However, their methods frequently included physical punishment rooted in evangelical beliefs about sin and compounded by imperial ideologies, were not uniformly effective. Records from the Basel Mission reveal significant resistance from the children, who often ran away, refused to cooperate, or sought intervention from their families. Such acts of defiance underscored the limitations of missionary authority and the disconnect between the missionaries’ intentions and the children’s aspirations for self-improvement.

Improved futures

The book is structured in five chapters, each focusing on the interactions between poor, marginalized caste communities and both missionary and government educators. A central theme is how formal schooling became increasingly linked to the notion of modern childhood and the potential for improved futures—not just for individuals, but for families, communities, and the emerging modern state. Discussions about poor children often framed them as lacking intellectual and moral resources, a deficit that education alone could not resolve. Nevertheless, education was seen to help these children develop the skills necessary to overcome the traits that perpetuated their struggles.

Formal education continues to play a crucial role in shaping ideals about what constitutes a "good" childhood and the standards of responsible parenting. Recent governmental and civil society initiatives in Kerala aimed at keeping children in school have successfully maintained high literacy rates over the past few decades. The emphasis on childhood as a precious asset and vulnerable citizen, especially concerning middle-class respectability, has led to increased scrutiny from the state and society, particularly regarding girls from poor and minority communities.

These shifts are also influenced by challenges such as rising unemployment, an aging population, and the influx of working-class migrants from eastern India, along with the looming threat of government school closures due to inadequate enrolment. As of 2021, nearly 3.5 million domestic migrant workers reside in Kerala, primarily from states like Assam, Bengal, and Odisha. This influx has prompted shifts in educational policy, as seen with the launch of Project Roshni in Ernakulam, which encourages migrant children to learn the regional language for educational and social integration until the fourth grade in government schools.

The long-term implications of these changes remain to be fully explored. In many ways, the perception of the poor child in Kerala is in flux, influenced by these demographic shifts. Compared to the historically rooted poor Malayali child, these migrant children from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds present a new challenge for educators striving to uphold the philosophy of universal schooling as central to modern childhood.

More Blogs

The Hawthornden Literary Retreat bestowed on Dr Sambudha Sen to complete the manuscript of a novel

Professor Sambudha Sen, Head of the Department of English at Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence, Delhi-NCR, was awarded a residency at the...

The Power of the Moving Body

Movement is an innate bodily action that humans have been exhibiting for the longest time. Long before language was invented, the body was the...

How Does A Multi-Disciplinary Approach To Education Enhance Learning And Prepare Students For A Multi-Faceted World?

In today’s world, where businesses are changing almost every day, it is the responsibility of educational institutes to provide holistic...