Social, Cultural and Political Undertones in the Temple Murals at Jammu: A Study of Religious Syncretism in the Iconography and Typology

Abstract

The historic Dogra empire was at the crucial crossroads of empires and political states such as the Khyber corridor on its west, Punjab in its south, Pahari kingdoms in its south-east and Tibet in its east, with the alpine range of Gilgit-Baltistan safeguarding its northern frontiers. This region is also marked by a diverse religious demography adhering to a variety of faiths including Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism and Buddhism. In the mid-19th century, a period marked by rising political turbulence in South Asia, the Dogra patrons constructed two major temples at Jammu, notable for their murals bearing Hindu, Islamic and Sikh sensibilities. The paper examines the various social, political, and diplomatic factors that influenced the commissioning of subject matter religiously syncretic in nature while considering factors such as the varying demography, personal inclination of the patrons, as well as the strife for political legitimacy of the Dogra dynasty.

Keywords: Jammu; Kashmir; Murals; Religious Syncretism; Dogra Dynasty; Pahari Painting

(All images in the paper belong to the author)

Introduction

Art has played a significant role throughout history as a dynamic medium for the expression of social, political, and personal narratives by both artists and patrons. This multifaceted function of art has evolved across different periods, serving as a platform for artists to articulate their angst, religious figures to disseminate divine messages, and politicians to shape narratives within societal discourse. Murals, in particular, emerge as a pivotal form of artistic expression within this broader context. Specifically designed to embellish public spaces, murals offer a visually compelling means of conveying messages to a broad audience, thereby facilitating the dissemination of ideas on a societal scale.

In South Asia, the inception of murals can be traced back to the ancient caves of Ajanta, dating to the 2nd century BCE. These early murals were crafted with a deliberate intent to propagate the fundamental tenets of Buddhism and depict tales of the Jataka. Until the modern era, the tradition of murals in South Asia remained predominantly confined to religious spaces, adorning the walls and ceilings of temples. Consequently, murals assumed a crucial role as a tool for the propagation of religious ideologies, shaping and reinforcing the spiritual landscape of the region. From this purview, the murals in two 19th century CE Hindu temples at Jammu deserve critical examination as they are laden with a unique intersection of subjects taken from Hindu mythology, while also incorporating elements from Islamic and Sikh tradition.

Temples at Burj and Sui

The two Vaishnava temples at Burj (Fig. 1) and Sui (Fig. 2) are located around 25 kilometres from Jammu city, and one kilometre from each other. Although documentary information pertinent to the construction of these temples is scant (for detailed documentation of the murals, see, Kour 2018), these are highly similar in style and architecture to the late 19th century temples of Raghunathji city (dated 1857 CE), and Ranbireshwara (dated 1878 CE).

Fig. 1 Temple at Burj, Jammu, mid-19th century

Hence, it is believed that the temples, most likely royal commissions, must have been erected around the same period. Maharaja Ranbir Singh of Jammu (r. 1857-85 CE) was known for his devout nature and Sanskrit learning and is credited with building several temples during his reign (Archer 1973: 181). Although a detailed account of the religious inclination of the Jammu rulers is not available, many temples dedicated to Rama during the reign of Maharaja Ranbir Singh indicate that the cult of Rama must have been favoured by the Jammu court.

Historical Background

The construction of temples in Jammu on such a grand scale must have a lot to do with the re-establishment of the Dogra dynasty in the Jammu hills. After the deposition of Raja Jit Dev (r. 1797-1812 CE) in favour of the Sikhs in 1812 CE, Jammu was annexed to the Sikh kingdom, with Prince Kharak Singh, son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh (r. 1801-39 CE), serving as the head of Jammu as a jagir till 1820 CE (Archer 1973: 181).

In 1820 CE, Ranjit Singh designated Gulab Singh Dogra, a descendant of the Jammu ruling family, as the Governor of Jammu and was granted Jammu town as a fief (Hutchison and Vogel 1933: 552).

Fig. 2 Temple at Sui Simbli, Jammu, mid-19th century

Following the Anglo-Sikh war (1845-1846 CE), Gulab Singh was recognised by the British in the Treaty of Amritsar as an independent Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir (Archer 1973: 181). Having devoted much of his reign towards annexing neighbouring states, no major architectural constructions are attributed to the reign of Gulab Singh. However, the reign of his son and successor Ranbir Singh (1857-85 CE) witnessed an era of political stability and economic prosperity. Under these circumstances, he was able to commission major architectural projects, as an indication of asserting a new era of Dogra political and cultural dominance.

History of Painting in the Jammu Hills

Painting, however, as a tradition, was not entirely novel to Jammu and its adjoining hill states during this period of Dogra resurgence. Portraiture in Jammu remained in vogue since the reign of Raja Dhrub Dev (r. 1703-1735 CE), as evident by a portrait of the Raja signed by painter Uttam. Miniature painting was already evolving in the neighbouring Pahari hill states such as Basohli, Chamba and Nurpur since the early 17th century CE (Ohri 1991: 3). After the rise of the Sikhs in the early 19th century CE, several Pahari painters of the Kangra valley migrated towards Lahore to seek patronage (Sharma 2010: 48). Khandalawala (1958: 192) has noted that from 1812 onwards, Sikh style of painting had prevailed in Jammu. There is also a likelihood of several painters migrating towards Jammu in search of patronage following the downfall of the Sikhs and the rise of Jammu as the paramount power in the North-Western Himalayas. The amalgamation of these distinct painter sensibilities has certainly contributed towards the blooming of a novel visual language as observed in the murals of the two Vaishnava temples.

Murals at the Sui Simbli Temple

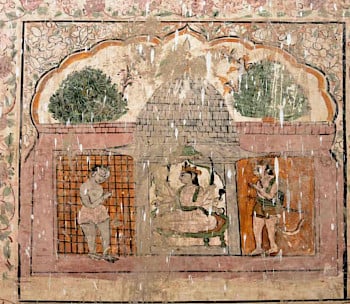

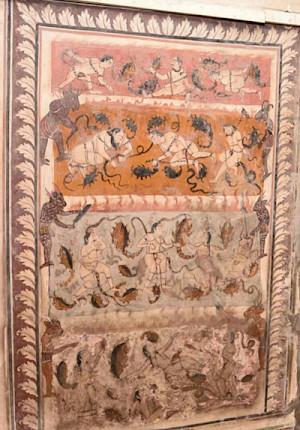

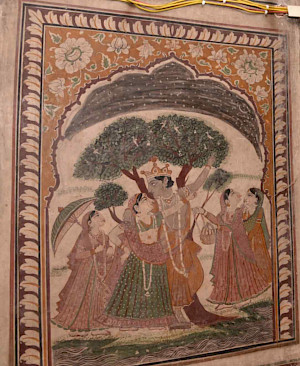

The shrine at Sui Simbli temple comprises a diverse subject matter from Hindu mythology, including depiction of various forms of the Devi (Fig. 3), scenes from hell (Fig. 4), episodes of krishna-lila (Fig. 5), Ramayana (Fig. 6) and medieval Hindi love poetry (Fig. 7). However, what is noteworthy is the depiction of two Sikh Gurus – Guru Nanak Dev (Fig. 8), the first Guru, and Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Guru (Fig. 9).

Fig. 3 Durga Enthroned, detail from a mural in the Sui Simbli temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 4 Scene of Hell, detail from a mural in the Sui Simbli temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 5 Kaliyadamana, episode from krishna-lila, detail from a mural in the Sui Simbli temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 6 Battle between the lanka Forces and the Monkey Army, episode from the Ramyana, detail from a mural in the Sui Simbli temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig.7 Krishna in an Amorous Union with Gopis, detail from a mural in the Sui Simbli temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 8 Guru Nanak Dev, the First Sikh Guru, detail from a mural in the Sui Simbli temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 9 Guru Gobind Singh, the Tenth Sikh Guru, detail from a mural in the Sui Simbli temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 10 Depiction of Perso-Islamic Mythological Beings, details from a mural in the Sui Simbli temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

A large mural panel in the site is dedicated to Perso-Islamic mythology (Fig. 10), including Solomonic peri figures, the Islamic Buraq, and the legend of Div Akvan and Rustam from Firdausi’s Shahnameh.

Murals at the Burj Temple

The murals in Burj temple surpass the murals in Sui Simbli temple in terms of both artistic merit and scale, exhibiting grandeur and monumentality. The subject matter is predominantly Vaishnavite in nature, with a lot of emphasis on signifying Vishnu as the supreme deity (Fig. 11). The most celebrated subject matter includes episodes from the Ramayana (Fig. 12), the tenth canto of the Bhagavata Purana (Fig. 13), depiction of Hell (Fig. 14) and couplets from medieval Hindi love poetry (Fig. 15). Irrespective of the predominantly Vaishnavite subject-matter, the murals do have space for Perso-Islamic themes, such as an entire ceiling depicting Persian peris gliding in the sky, as well as Mughal arabesque designs (Fig. 16). In several instances figures of Hindu mythologies can also be seen encapsulated in Mughal cartouches (Fig. 17).

Fig. 11 Vishnu and Lakshmi Enthroned, detail from a mural in the Burj temple, Jammu, c. mid 19th century

Fig. 12 Parashurama Confronts Rama, episode from the Ramayana, detail from a mural in the Burj temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 13 Krishna slays the Demon-king Kamsa, episode from the Bhagavata Purana, detail from a mural in the Burj temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 14 Scenes of Hell, detail from a mural in the Burj temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 15 Krishna with Gopis in Vrindavan, detail from a mural in the Burj temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 16 Persian Peris, detail from a mural in the Burj temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Fig. 17 Devi depicted within a Mughal cartouche, detail from a mural in the Burj temple, Jammu, c. mid-19th century

Religious Syncretism in the Subject Matter

The salient feature observed in the two examined sites is the remarkable incorporation of themes from Islamic as well as Sikh traditions in harmony with the predominantly Vaishnava subject matter. Rather than presenting an impression of contrived juxtaposition, the integration appears seamless, unfolding organically. The visual syncretism exudes an element of natural cohesion, suggesting the cohabitation of Hindu, Islamic and Sikh sensibilities as unobtrusive, especially considering that the temples were erected in a period marking the beginning of heightened communal conflicts. The underlining aspects dictating the subject matter in the murals appear to be chiefly influenced by the social and demographic construction of the Dogra empire, personal inclinations of the patrons, and the pursuit of political legitimacy by the Dogras.

Social Aspects

Jammu, as a state, exhibited a long-standing cosmopolitan character, despite its predominantly Hindu demographic. The 16th century witnessed a significant development in this regard, as the Muslim dargah of Peer Mitha was established under the patronage of Raja Ajaib Dev (r. 1436-59 CE) as an expression of reverence for Sufi saints. This early gesture not only exemplified religious tolerance but also marked the incorporation of Islamic elements within the cultural fabric of the region. The Sikh influence, on the other hand, had been evident in the state's affairs since the reign of Sampuran Dev (r. 1787-97 CE), with active Sikh participation in governance until its annexation by Ranjit Singh in 1812 CE. Subsequently, the Dogras, upon assuming control of predominantly Muslim Kashmir in 1846 CE, found themselves immersed in a diverse demographic landscape. This intricate interplay of cultures and religions within the dominions is artfully depicted in the murals of the two temples, attesting to the patron Ranbir Singh’s engagement with and understanding of the pluralistic nature of his realm.

Inclusive Nature of the Patrons

Vigne (1842: 184) recorded that Maharaja Gulab Singh of Jammu,

“has made himself feared by his cruelty and tyrannical exactions but affects to be tolerant and liberal in his religious opinions. Jammu is, accordingly, the only place in the Panjab where the Mulahs may call the Musulmans to prayers. Runjit [Singh] had forbidden them to do so, but Gulab Singh, his powerful vassal, allowed them to ascend the minars of Jammu, in the exercise of their vocation.”

The religious inclusivity extended into the reign of Maharaja Ranbir Singh, the son and successor of Gulab Singh, who employed pandits and maulavis to translate and transliterate religious texts, of which 5,000 were catalogued by MA Stein (Bakshi 1998: 88). As Dogras were also closely associated with Maharaja Ranjit Singh, they must have also held a profound reverence for Sikhism. This historical context illuminates their inclusive approach, a sentiment that resonates in the murals of the two temples where due space is accorded to reflect these religious sensibilities.

The Dogra Dynasty and Political Legitimacy

The concept of political legitimacy also has a crucial role to play. Political legitimacy in kingship is rooted in the belief that a ruler’s authority is justifiable and accepted by the governed population. It serves as a crucial foundation for stable governance, social order, and the ruler’s ability to exercise power without constant resistance. It could be derived from various sources, including hereditary claims, religious endorsement, or popular support.

Raja Gulab Singh, though belonging to the ruling Jamwal family of Jammu, was not a direct descendant of Jit Dev (r. 1797-1812 CE), the last sovereign of Jammu state, but was the fourth-generation descendant of Raja Dhrub Dev (r. 1703-1735 CE), thus having no claim to the throne. He left Jammu in 1809 CE and joined the Sikh army in Lahore. Rising rapidly up the ranks, he held a key role in Ranjit Singh’s government and was designated Raja by Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1820 CE (Archer 1973: 181). The period between 1812, the dissolution of the Jamwal authority by the Sikhs, and 1820 CE marks an era of rising Sikh involvement in the social and political fabric of Jammu. Hence, the religious syncretism and inclusivity in the murals of Burj and Sui Simbli temple can simultaneously be interpreted as Ranbir Singh’s attempt to justify his rule to the Suryavamsi Rajputs of the Jamwal dynasty by incorporating Ramayana murals, thus constructing a genealogical link with the ruling house, incorporating Sikh subject-matter to indicate a political affiliation with the Sikhs, and including Perso-Islamic subject-matter to appear culturally attuned to the significant Muslim population of his dominion.

Conclusion

The integration of Muslim and Sikh subject matter within Vaishnava temples during Dogra rule emanated from a nuanced interplay of cultural diffusion, artistic collaboration, and a pronounced commitment to religious pluralism. Beyond the described considerations of political legitimacy and personal proclivities, the heterogeneous cultural influences prevalent in the region likely facilitated an organic amalgamation of diverse styles and thematic elements. It is also noteworthy that the migration of Pahari painters towards Lahore and the ensuing artistic dialogue could have manifested in a cross-cultural exchange, thereby resulting in religious syncretism. The discernment exhibited by Maharaja Ranbir Singh in accommodating such diverse elements is reflective of a deliberate attempt to convey a message of inclusivity and reverence for the manifold religious traditions permeating his dominion. Consequently, the temple murals transcend mere artistic expressions, and assume the role of visual documentary evidence of the harmonious cohabitation of distinct religious communities under the Dogra rule.

A continued tradition of religious syncretism is still prevalent in the region in the form of worship at Sufi shrines. These “shared sacred spaces” (Chowdhary 2021) contribute to harmonious inter-community relations. These shrines, observes Chowdhary, provide the freedom of participation to different communities and subvert the process of rigid religious exclusivity on the one hand and extreme radicalisation on the other.

References

Archer, William G. 1973. Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills: A Survey and History of Pahari Miniature Painting: Vol. I. Sotheby Parke Bernet, xxiii.

Bakshi, S.R. 1998. Kashmir: History and People. Sarup and Sons.

Chowdhary, R. 2021. The shared sacred spaces in Jammu region in A. Chauhan (ed). Understanding Culture and Society in India: A Study of Sufis, Saints and Deities in Jammu region. Singapore. Springer.

Hutchison, J., and Vogel, J. Ph. 1933. History of The Panjab Hill States: Vol. I. Superintendent Government Printing.

Khandalawala, Karl J. 1958. Pahari Miniature Painting. The New Book Co. Private Limited.

Kour 2018. Documentation of murals in Medieval Temples of Jammu. Retrieved from https://www.sahapedia.org/saha-user/navjot-kour

Ohri, V. C. 1991. On the Origins of Pahari Painting: Some Notes and a Discussion, Indian Institute of Advanced Study in association with Indus Pub. Co. New Delhi.

Sharma, Vijay. 2020. Kangra Ghati Ki Chitrankan Parampara. (Hindi). Chamba Shilpa Parishad.

Vigne, G. T. 1842. Travels in Kashmir, Ladak, Iskardo, the Countries Adjoing the Mountain-course of the Indus and the Himalaya, North of the Panjab. Henry Colburn.

About the Author: Navjot Kour is currently a post-doctoral researcher at the Catalan Institute of Classical Archaeology, Tarragona, Spain. Her research focuses on the Archaeological Investigation of the Outer Plains of Jammu (India), with the primary goal of identifying the archaeological legacy of the area and comprehending the early inhabitants’ landscape adaptation techniques.