Issue no. 17

August 2025

Livelihoods in Transition: The Changing Balance of Tourism and Agriculture in Ladakh

Abstract

Ladakh is undergoing a major shift from traditional agro-pastoral livelihoods to tourism-driven development. This issue brief explores how these two sectors—combined farming and tourism—interact, highlighting both synergies and trade-offs. Through a comparative SWOT analysis and review of recent ecological and institutional changes, this piece identifies challenges such as ecological stress, cultural erosion and planning gaps. It proposes strategic convergence pathways that integrate ecological sustainability, community-led governance and inclusive economic planning, aiming to build resilient, hybrid livelihoods suited to Ladakh’s fragile high-altitude environment.

Keywords: Ladakh; combined farming; tourism; sustainable livelihoods; SWOT analysis

Introduction

Leh, the district headquarters of Ladakh, lies within a high-altitude cold desert characterized by limited access to freshwater, arable land and vegetation. Historically, Ladakh’s communities adapted to these constraints through combined mountain farming—a tightly integrated system of agriculture and pastoralism rooted in ecological knowledge, social reciprocity and customary rules. This system not only supported household food security but also sustained the fragile ecology by enhancing soil fertility, regulating nutrient flows and preserving biodiversity. Agro-pastoralism in Ladakh was uniquely adapted to its environment. Crops such as barley, buckwheat and peas were cultivated in micro-irrigated fields, while livestock herding—especially yaks, sheep, goats and dzos —enabled nutrient recycling and mobility across ecological zones. The shared management of resources through institutions like goba (village heads) allowed equitable access to scarce resources. Importantly, this diversity provided resilience against environmental shocks and socio-economic fluctuations, sustaining communities in an otherwise inhospitable terrain (Ladon et al. 2023).

This Issue Brief examines the complementarity and trade-offs between agro-pastoralism and tourism. It uses a comparative SWOT analysis to outline sectoral strengths and limitations, reviews recent trends in ecological and livelihood change and recommends strategic pathways for convergence. The goal is to support policy dialogues on sustainable livelihoods and ecosystem governance in Ladakh and similar high-altitude regions.

Tourism and Impact on the Environment

Tourist inflows to Ladakh have been steadily increasing over the past two decades, driven by improved accessibility, policy support and growing global interest in Himalayan landscapes. Tourism contributes around 50% to Ladakh’s GDP – as per estimates, the tourism sector was valued at Rs.600 crore in 2020 (Tourism Vision 2022). In October 2024, Ladakh reported the highest year-on-year growth in regional GST revenue at 30%, reflecting the growing role of tourism in its economy (IBEF 2024).

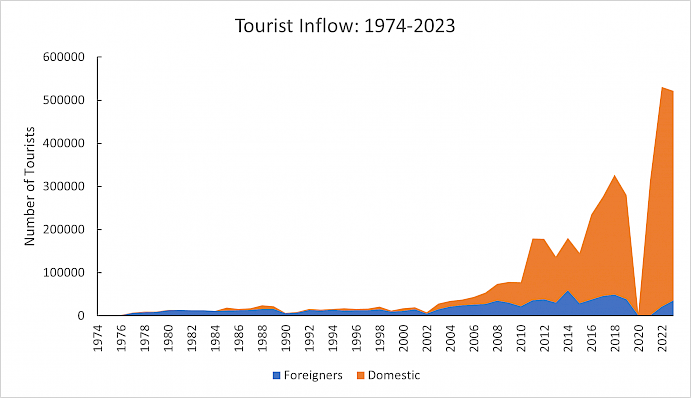

Since the 1970s, Ladakh has become increasingly integrated with national and global economic systems, with tourism becoming a key source of income (Figure1; IISD 2020). Improved infrastructure and policy incentives have led to a surge in visitor numbers, enhancing transportation access and generating livelihood, particularly for young people. However, this growth has also intensified environmental pressure; the expansion of roads, accommodation and services has often gone beyond what local resources—especially, water and land—can support, raising concerns about sustainability (BORDA and LEDeG 2019; Campbell 2020; South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People 2022).

Figure no. 1

Tourists inflow since 1974–2023

Source: Ministry of Tourism, Government of India 2022|

Despite Ladakh’s evolving developmental trajectory, structural vulnerabilities persist and both tourism and traditional livelihoods continue to coexist in a state of tension and transition. The Tourism Ministry’s revamp of the Swadesh Darshan Scheme into Swadesh Darshan 2.0, focuses on sustainable and responsible tourism. Leh and Kargil have been identified as priority destinations under this initiative, reflecting the shift toward integrated and eco-sensitive tourism planning in the region (Ministry of Tourism 2023). The region remains heavily dependent on external food supplies, with over 70% of its food demand met through imports. Tourism, though a key contributor to GDP (50%), remains seasonal and ecologically intensive (Ladakh Vision 2050). These trends are further compounded by the lack of integrated monitoring and regulatory frameworks, highlighting the urgent need for coordinated and sustainable livelihood planning.

Recent policy developments, however, indicate a growing recognition of the need to align tourism with ecological and cultural priorities, while also fostering cross-departmental coordination. For instance, the Ladakh Mountaineering Policy (2024) promotes responsible mountaineering through operator accreditation, ecological safeguards and skill development for remote communities. It is led by the Tourism Department in collaboration with other UT agencies, reflecting an integrated approach. Similarly, the revised Ladakh Homestay Policy (2023–24) supports eco-friendly and culturally rooted tourism by backing over 900 homestays, with a target of 10,000 visitors. It includes provisions for protected areas and winter tourism and is being jointly implemented by the Wildlife and Tourism Departments. Notably, the homestay policy’s emphasis on traditional cuisines and locally-sourced resources opens up possibilities for synergies with farming and organic products value chains.

These examples suggest an emerging convergence between tourism planning and broader environmental governance, including collaborative efforts on issues such as pollution and resource use. Together, these initiatives point to an emerging livelihood frontier where agriculture and tourism may mutually reinforce each other. Farm-based tourism, food trails and the promotion of GI-tagged products illustrate how the experiential value of tourism can be integrated with the ecological and cultural significance of traditional practices. This evolving convergence offers Ladakh a unique opportunity to craft an integrated development pathway—one that is economically resilient, environmentally sustainable and heritage-based.

Synergies and Trade-offs: SWOT of Livelihood Sectors in Ladakh

Ladakh’s economy is increasingly structured around two primary sectors: traditional combined farming (agriculture and pastoralism) and tourism. While both have distinct socio-ecological roots, their future viability depends on how their strengths are integrated and vulnerabilities addressed. A comparative SWOT analysis, informed by recent studies and policy documents, highlights key dimensions for livelihood planning (Table no. 1).

Table no. 1

Comparative SWOT of traditional (combined farming) versus emerging economy (tourism) in Ladakh.

|

Aspect |

Combined Farming |

Tourism |

|

Strengths |

• Deep ecological knowledge • Low carbon and water footprint • Supports local food security and cultural continuity |

• High income potential • Expands market linkages and exposure • Youth engagement and service sector diversification |

|

Weaknesses |

• Labour-intensive, especially during harvest • Low productivity due to climatic limitations • Limited mechanization and policy neglect |

• Seasonal and highly volatile • High resource consumption • Generates uneven benefits; risks overdependence |

|

Opportunities |

• Organic certification and GI-based marketing • Agro-tourism and traditional food trails • Promotion of climate-resilient crop varieties |

• Growth in sustainable and cultural tourism niches • Homestays linked to local crafts and food • Emerging local eco-tourism norms and community-led models • Green job creation through eco-infrastructure |

|

Threats |

• Youth outmigration • Increasing climatic stress and glacier retreat • Institutional weakening and land use change |

• Infrastructure strain and pollution • Resource conflicts with farming and herding • Cultural commodification and authenticity loss |

Sources: Compiled from (UT Ladakh (2020,2024 and 2025); BORDA and LEDeG 2019; IISD 2025; Kothari and Deachen 2024; Ladon et al. 2023; LAHDC 2025; Ministry of Tourism (2022 and 2023) and South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People 2022)

This SWOT analysis reveals that combined farming and tourism, while distinct in form, are deeply interconnected in function and impact. Agro-pastoralism contributes ecological stability, embedded knowledge systems and food security but struggles with low monetization, labour constraints and youth out-migration. Tourism, on the other hand, brings market linkages, income diversification and greater youth engagement, but its seasonal and resource-intensive nature exerts pressure on the same land, water and cultural systems that sustain traditional livelihoods.

A decentralised or sectoral approach risks exacerbating these tensions. For example, tourism expansion in absence of robust farming systems may reduce the community’s adaptive capacity—particularly during external shocks such as, for example, the Covid-19 pandemic. While the sudden halt in tourism disrupted household incomes, traditional food storage practices provided temporary buffers, underlining the continuing relevance of traditional agro-pastoral practices and resilience.

An integrated approach, therefore, becomes necessary—not simply for coordination but to leverage complementarities and mitigate shared vulnerabilities. The challenge is now to bridge gaps—by reducing labour burdens in agriculture, improving the sustainability of tourism and institutionalizing mechanisms for mutual reinforcement. If effectively implemented, such an approach can enhance long-term ecological and economic resilience by balancing continuity with innovation.

Way Forward

The shift from subsistence agro-pastoralism to service-oriented tourism in Ladakh is reshaping socio-ecological systems in visible and subtle ways. Spatially, the transition is more pronounced near tourist centres like Leh, Nubra and Pangong Tso, while many remote and higher-altitude villages remain more reliant on farming and herding. These spatial disparities create unequal access to services, infrastructure and markets, compounding existing socio-economic hierarchies.

Tourism is not only transforming Ladakh’s economy but also reshaping its cultural and social fabric. It has expanded livelihood avenues, particularly for the younger men in hospitality, transport and construction. However, it has also shifted labour burdens in farming toward older women and migrants, a common phenomenon across Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) (Roy et al. 2022). The growing emphasis on cash-based income has contributed to weakening of traditional institutions, such as the role of customary councils in land and water governance. As decision-making becomes increasingly market-driven, the erosion of these embedded institutions reduces the scope of inter-generational knowledge sharing and collective resource management (Ladon et al. 2023; Ladon 2025). In this context, tourism is not just an economic force, but a cultural and institutional disruptor necessitating thoughtful planning to retain community cohesion while promoting diversification.

Land-use changes—combined with expanding tourism infrastructure and water extraction—are also reshaping biomass cycles and groundwater dynamics. Increased fencing of farmlands, expansion of roads and conversion of fallow land into camps and resorts have disrupted livestock corridors and common property resources. A growing reliance on borewells for guesthouses and hotels to support increased tourism is stressing aquifers. The decline in livestock also reduces organic manure availability, leading to growing dependence on imported fertilizers. Empirical assessments also confirm these pressures. Geneletti and Dawa (2009), using a GIS-based environmental impact assessment, mapped tourism-related stressors such as trail erosion, grazing, waste dumping and off-road driving. Their study highlights that ecologically sensitive zones—particularly in central and south-eastern Ladakh—are highly vulnerable, calling for stronger spatial planning and regulatory safeguards. Climate change further compounds these challenges. Erratic snowfall, glacial retreat and flash floods have increased in recent decades (IMD 2021). Such events disrupt both farming and tourism. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the vulnerabilities of tourism dependence, while also reviving interest in local food systems, seed banks and collective farming—highlighting the value of diversified livelihoods.

In Zanskar, these ecological pressures are also intersecting with wildlife dynamics. Pasture shrinkage, changing land use and increased human presence have contributed to a rise in wildlife-livestock conflicts —particularly involving snow leopards and Himalayan brown bears. In response, communities supported by NGOs have adopted mitigation strategies such as predator-proof corrals, solar deterrents and compensation mechanisms (Kothari 2022). Simultaneously, conservation-linked tourism, including wildlife-focused homestays, is being promoted as a complementary livelihood model. These efforts aim to turn wildlife presence from a liability into a livelihood opportunity, by promoting conservation-linked tourism such as wildlife homestays and winter tourism—particularly snow leopard-based tourism, which has become a key source of income during the lean season.

However, significant policy gaps persist. Planning remains top-down, poorly aligned with local contexts. The Tourism Vision for Ladakh (2022) lacks enforceable ecological thresholds and was developed with limited community input. It acknowledges the absence of assessments on sustaining tourism services without causing environmental harm, along with ecological impact data—tools critical for sustainable destination planning. Further, weak cross-departmental coordination limits the integration of agriculture, tourism and environmental strategies.

As a result, alternative approaches by civil society groups and trade or travel associations have emerged to promote responsible tourism models that benefit the broader community while mitigating adverse impacts. Several local enterprises—such as Ladakh Basket, Reetstot and Looms of Ladakh—as well as non-profit organisations like the Women’s Alliance of Ladakh and Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust (SLC-IT), have actively filled institutional and policy gaps through bottom-up approaches. For instance, SLC-IT’s collaboration with the Wildlife Department to promote community-based snow leopard tourism demonstrates how conservation and livelihoods can be aligned through coordinated planning (Kothari and Deachen 2024). These initiatives are gradually reshaping relationships with state agencies and tourism administrators: in some cases complementing official efforts and in others, highlighting the need for more institutionalised platforms for joint decision-making and long-term integration.

Notably, emerging initiatives such as Ladakh Basket Agro-Stay and Himalayan Farmstays demonstrate how sustainable tourism can reinforce farming (Wangchuk 2021; Himalayan Farmstays 2025). These models enable visitors to participate in agricultural activities, support rural livelihoods and promote ecological awareness. Similarly, the use of MGNREGA funds to build ice-hockey rinks for winter tourism reflects the potential of multi-sectoral planning. Nevertheless, such innovations remain scattered and largely driven by individual or civil society rather than being supported through coordinated policy frameworks. This signals a broader challenge, namely, the lack of institutional coherence and sustained local participation in mainstream planning. Without mechanisms to scale and integrate these efforts, the potential for genuine agriculture-tourism synergy remains under-realised.

Policy Landscape and Strategic Recommendations

While local innovations provide valuable insights, policy frameworks at the UT level remain fragmented. Ladakh’s evolving development strategy reflects growing recognition of the need for low-impact, inclusive growth. Key policies—such as the Ladakh Vision 2025, Carbon Neutral Ladakh Mission, STP Incentive Scheme, Homestay Policy (2021-22 and 2022-23) and Mission Organic initiatives—offer a foundational framework for promoting convergence across tourism, agriculture and conservation. These schemes support eco-friendly infrastructure, women-led enterprises and promotion of local produce. However, their transformative potential is limited by weak inter-departmental coordination and limited community participation.

Some initiatives reflect the administration’s recognition of the need to strengthen agriculture alongside tourism. In 2020, Ladakh UT Administration directed officials from the departments of Tourism and Animal/Sheep Husbandry and Fisheries, along with All Ladakh Tour Operator Association, to jointly explore ways to integrate livestock based livelihoods into eco-tourism and rural experience itineraries (Reach Ladakh 2020). This initiative marked early steps towards cross-sectoral planning. A year later, during the launch of Organic Farmer Facilitation Centres in both the districts, the then Ladakh Lieutenant Governor stated, “The commercial development of the agriculture sector is vital for the economy of Ladakh, as tourism has proven to be uncertain recently and it is best to give importance to the primary sector” (Administration UT Ladakh 2021). While this remark underscores a renewed focus on agriculture, it also reinforces the need for long-term strategies that view agriculture and tourism not in isolation, but as complementary pillars of Ladakh’s economy.

Recommendations:

- Cross-Sectoral Coordination and Participatory Budgeting

Establish institutional platforms at block and district levels involving tourism and key primary sector departments such as agriculture, wildlife and rural development. Introduce participatory budgeting to align schemes with livelihood priorities. The Ladakh Homestay Policy serves as a successful example of collaboration between tourism and wildlife departments in conservation priority areas.

- Inclusive Capacity Building for Rural Livelihoods

Scale up region-specific training in agro-processing, eco-tourism, digital literacy and enterprise development, with targeted modules for women and youth. Content must be delivered in local languages and tailored to Ladakh’s high-altitude contexts. Partnerships with NGOs, universities and industry stakeholders can improve quality and reach.

- Institutional Revitalization and Youth Engagement

Recognize and strengthen customary roles such as the Goba in governing local resources as well as preserving traditional practices. Intergenerational linkages can be built through apprenticeships and knowledge-sharing programs, connecting youth with elders. Youth entrepreneurship in sustainable agriculture and green tourism should be promoted through mentorship and start-up grants.

- Integrated Infrastructure and Ecological Regulation

Promote shared infrastructure—such as solar-powered cold storage, decentralized waste treatment and rainwater harvesting—in tourism and agriculture clusters. Tourism-related permits should be linked to environmental compliance (e.g., composting toilets, green construction). Joint infrastructure planning can minimize aquifer stress and reduce land-use conflicts.

- Agri-Tourism Zoning and Thematic Linkages

Develop GIS-based zoning frameworks to guide spatial planning for agro-tourism, ensuring compatibility with farming, conservation and mobility patterns. Incentivize homestays, farm-stays and food trails that celebrate Ladakh’s agro-cultural heritage. GI certification and local branding should be expanded through coordinated marketing platforms.

- Research on Carrying Capacity and Impact Assessments

Commission interdisciplinary research on tourism carrying capacity, land and water use thresholds and climate vulnerability at sub-regional scales. This data should inform regulatory guidelines and adaptive management plans. Community institutions and local universities should be involved in designing and monitoring these assessments.

Conclusion

Ladakh’s development crossroads reflect a deeper question—how can a fragile mountain region sustain livelihoods without compromising its ecological integrity? Agro-pastoralism and tourism need not exist in silos. Combined farming offers ecological stewardship and cultural continuity, while tourism brings income and infrastructure. However, without coordination, both risk undermining each other.

To avoid this, Ladakh needs a data-driven, landscape-based planning approach that identifies ecologically and socio-economically coherent zones—such as valleys, pasture belts and highland settlements—and tailors interventions accordingly. For example, agricultural valleys could integrate GI-tagged crops with food trails and markets, while highland pastures and wetlands could support rotational grazing and wildlife tourism. Such planning should draw on geospatial mapping, long-term ecological monitoring and community knowledge.

The recent launch of the Ladakh State Data Centre and State Wide Area Network provides essential infrastructure to integrate such datasets (National Informatics Centre, Ladakh 2024). While still nascent, these platforms could support coordinated governance by linking data on water, tourism, biodiversity and agriculture.

Crucially, data must enable decentralized governance. Block-level planning bodies—comprising village representatives, line departments and researchers—should be empowered to interpret local data and set development priorities. In this way, Ladakh can build adaptive institutions that align livelihoods with sustainability, setting an example for other high-altitude regions.

REFERENCES

Administration of Union Territory of Ladakh. 2020. ‘Vision 2050 for Ladakh Union Territory’. September. https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s395192c98732387165bf8e396c0f2dad2/uploads/2020/09/2020092627.pdf

Administration of Union Territory of Ladakh. 2021. ‘Ladakh Gets Organic Farmer Facilitation Centers in Both Districts’. 3 July. https://ladakh.gov.in/ladakh-gets-organic-farmer-facilitation-centers-in-both-districts/

Administration of Union Territory of Ladakh. 2024. ‘Ladakh Administration Approves Annual Action Plans for Centrally Sponsored Schemes of Agriculture Department’. 17 May. https://ladakh.gov.in/ladakh-administration-approves-annual-action-plans-for-centrally-sponsored-schemes-of-agriculture-department/

Administration of Union Territory of Ladakh. 2025. ‘Efforts on to Make Ladakh Carbon Neutral: Advisor Ladakh Reviews Implementation Status of Action Plan Prepared by Departments’. 17 June. https://ladakh.gov.in/efforts-on-to-make-ladakh-carbon-neutral-advisor-ladakh-advisor-ladakh-reviews-implementation-status-of-action-plan-prepared-by-deptts/

BORDA and LEDeG. 2019. ‘Water in Liveable Leh! Final Report 2019: Assessment of Water Supply, Sanitation, and Wastewater Management in Leh Town’. Bremen Overseas Research and Development Association—South Asia. December. https://borda.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/06.01.-Water-In-Liveable-Leh-2019.pdf

Campbell, A. V. 2020. ‘Integrated Urban Water Management (IUWM) – Rapid Assessment – Leh, India’. BORDA South Asia and LEDeG. April. https://borda.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/06.07-IUWM-Rapid-Assessment-Leh-India.pdf

Geneletti, D, and D. Dawa. 2009. ‘Environmental Impact Assessment of Mountain Tourism in Developing Regions: A Study in Ladakh, Indian Himalaya’. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 29(4): 229–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2009.01.003

IBEF. 2024. GST Mop-up Sees Six-Month High in October with ₹1.87 Trillion, up 8.9 % Y-o-Y. Indian Brand Equity Foundation, November. https://www.ibef.org/news/gst-mop-up-sees-a-six-month-high-in-october-with-us-22-28-billion-rs-1-87-trillion-up-8-9-yoy

International Institute for Sustainable Development. 2025. ‘Leh Water Supply Management Workshop Master Document’. 10-12 September. https://ladakh.iisdindia.in/pdf/IISD%20Leh%20Water%20Supply%20Management%20Workshop%20Master%20Document%201.pdf

Kothari, A, and K. Deachen. 2024. ‘Can Ladakh Embrace Tourism While Protecting Its Fragile Ecosystem?’ Outlook Traveller, 26 April. https://kalpavriksh.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Can-Ladakh-Embrace-Tourism-While-Protecting-Its-Fragile-Ecosystem_-Outlook-Traveller-26.4.2024.pdf

Kothari, A. 2022. ‘Rebuilding Co-existence: Snow Leopard, Brown Bear and Human Interactions in Zanskar, Ladakh’. Sanctuary Asia 42(6): 68–71. https://kalpavriksh.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Zanskar-wildlife-human-conflict-article-Sanctuary-June-2022.pdf

Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council. 2025. ‘Policies and Schemes’. District Leh, UT of Ladakh. https://leh.nic.in/tourism/policies-and-schemes/

Ladon, P, M. Nüsser, and S. C. Garkoti. 2023. ‘Mountain Agropastoralism: Traditional Practices, Institutions and Pressures in the Indian Trans‑Himalaya of Ladakh’. Pastoralism 13(1): 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-023-00245-6

Ladon, P. 2025. ‘Eroding Pillars: The Status of Local Institutions in Resource Management in Leh’. Issue Brief No. 10, May. Centre of Excellence for Himalayan Studies, Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence. https://snu.edu.in/centres/centre-of-excellence-for-himalayan-studies/research/eroding-pillars-the-status-of-local-institutions-in-resource-management-in-leh

Ministry of Tourism, Government of India. 2022. ‘Tourism Vision for Ladakh’. 10 February. https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s395192c98732387165bf8e396c0f2dad2/uploads/2022/02/2022021015.pdf

Ministry of Tourism, Government of India. 2023. ‘Swadesh Darshan 2.0: Development of Sustainable and Responsible Tourism Destinations’. Press Information Bureau, 22 November. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2004038

National Informatics Centre, Ladakh. 2024. ‘The Advisor to the Hon’ble LG Ladakh inaugurates Ladakh State Data Centre and Ladakh SWAN HQ’. 4 October. https://nicladakh.nic.in/event/the-advisor-to-the-honble-lg-ladakh-inaugurates-ladakh-state-data-centre-and-ladakh-swan-hq/

Reach Ladakh. 2020. ‘Administrative Secretary, Ladakh, Plans to Integrate Animal Farm Sector with Tourism Industry’. Reach Ladakh, 23 December. https://www.reachladakh.com/news/social-news/administrative-secretary-ladakh-plans-to-integrate-animal-farm-sector-with-tourism-industry?

ResponsibleTourismIndia.com. 2025. ‘Himalayan Farmstays’. https://www.responsibletourismindia.com/stay/himalayan-farmstays/339

Roy, N, V. Upadhyay, P. Kandari, V. Pala, and C. Kashyap. 2022. Thematic Study-I: Enumeration and Valuation of the Economic Impact of Female Labour in the Hills. A study of the Indian Himalayan Region assigned by NITI Aayog, funded by UGC. Submitted by Indian Himalayan Central Universities Consortium (IHCUC). February. https://www.hnbgu.ac.in/sites/default/files/2024-09/Theme-1.pdf

South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People. 2022. ‘J&K & Ladakh Cloud Bursts 2022: Missing Monitoring & Mitigation’. 12 December. https://sandrp.in/2022/12/12/jk-ladakh-cloud-bursts-2022-missing-monitoring-mitigation/

UT Ladakh. 2021. Conference on ‘Mission Organic and Launch of Organic Initiative’ Held in Leh Today: CEC Leh Launches Organic Initiative ‘Ser‑Lakmo’. 2 August. https://ladakh.gov.in/conference-on-mission-organic-and-launch-of-organic-initiative-held-in-leh-today-cec-leh-launches-organic-initiative-ser-lakmo/

Wangchuk, Rinchen Norbu. 2021. ‘How 3 Friends Are Helping Ladakhi Farmers Earn More by Staying Home’. The Better India. 20 September. https://thebetterindia.com/262569/ladakh-basket-organic-buy-leh-apricot-buckwheat-tea-farmers/

About the Author: Dr Padma Ladon is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Centre of Excellence for Himalayan Studies, Shiv Nadar University, Delhi-NCR. She holds a PhD in Environmental Science from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Specializing in plant ecology, she focuses on the high-altitude landscape ecosystems.

Share this on: