Issue no. 27

February 2026

Divided by Design: Segregated Municipal Water Access in Darjeeling Town

Abstract

The Eastern Himalayan Region (EHR) gets 2,500-3,000 mm of rainfall but faces water scarcity and Himalayan cities like Darjeeling have limited access to water. Like other Global South post-colonial cities, access in Darjeeling is uneven due to resource rights, property ownership, and location – private water connections are now a luxury, shifting from basic needs to status symbols. This issue brief examines Darjeeling's water scarcity, focusing on infrastructure, governance, and household conditions. It highlights the lack of last-mile connectivity and governance issues that fragment water management, resulting in ineffective projects and stifled innovation. It argues that enabling innovative infrastructure and institutions with political support is crucial.

Keywords: formal institutions; urban governance; households; spatiality; connectivity

The Eastern Himalayan Region (EHR) receives the highest rainfall within the Himalaya and India (Bhutia 2017). It receives between 2,500 and 3,000 mm of rainfall annually. Yet communities have faced water scarcity for decades. The Himalaya are often called water towers but this narrative frequently overlooks mountain communities and their lack of water access. These communities mainly depend on groundwater resources, such as springs, rather than surface water sources like rivers. Himalayan cities like Darjeeling face a paradoxical situation of having abundant water but limited access (Lama and Lama 2025; Chakraborty 2018; Rasaily 2014).

In addition to the Himalayan cities facing water scarcity, studies have also highlighted the uneven experiences of water scarcity in post-colonial cities of the Global South (Castan Broto et al. 2012; Domenech et al. 2013; Joshi 2014; Mehta et al. 2011; Mukherjee and Chakraborty 2016; Narain and Singh 2019; Samanta and Koner 2016; Sultana 2013; Larkin 2013; Meehan 2014; Ranganathan 2015). This disparity in unequal water accessibility for the communities results from a combination of years of irregular service provision and the current infrastructure at both the city and household levels (Millington 2018). Water scarcity experiences vary because factors such as resource entitlements, property rights, and location influence different societal groups differently (Alankar 2013; Anand 2011; 2001).

This issue brief explores the paradoxical situation in Darjeeling by examining the current state of its formal water infrastructure. Focusing on institutions and households, to understand the institutional aspects of water governance, this issue brief examines state projects and investments. Household characteristics, such as the legal and financial requirements of communities, are assessed next along with their biophysical locations; these indicate the absence of effective last-mile connectivity, which continues to drive differential water access today.

This issue brief draws on long-term ethnographic fieldwork conducted from 2014 to 2025 and secondary data sources. Primary data were collected through participant observations, household questionnaires, topic-guided interviews, and transect walks. Transect walks were conducted throughout the town to understand its layout and document the water services available. Secondary data came from municipal and state project reports, pamphlets, water management scheme documents, water connection forms, newspapers, reports from the Government of India’s Planning Commission, and relevant literature. The study also evaluates schemes commissioned by the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), PHE, and the Department of Municipal Affairs.

Darjeeling Town and its Colonial Water Systems

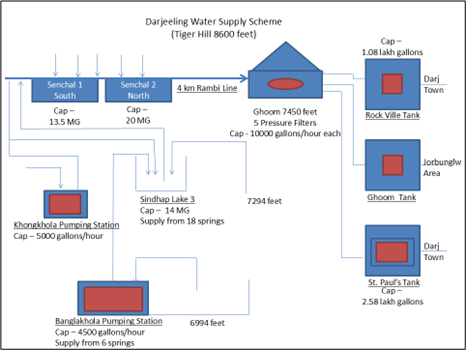

Darjeeling Town is located in a district that shares its name. Established in 1850, it was one of the first municipalities to be created by the British. Between the early 1900s and 1916-17, the British built the first water system for Darjeeling. This included two supply reservoirs, North and South Lakes, within the Senchal Wildlife Sanctuary, around 15km away from the town centre (Figure 1). The lakes are fed by 32 springs within the Sanctuary. The supply system connected the supply reservoirs to the two distribution tanks in town, located at St. Paul’s and Rockville.

* mg – million gallons

The system was designed to serve approximately 10,000 people. The population, according to the last census, was 1,20,000 people (Census 2011). With no census conducted since then, the current population data is unclear. 24 out of the 32 municipal wards have 88 slums and informal settlements (Rai 2015) and there is an overlap between the total BPL (Below Poverty Line) population and the slum population.

The Water Works Department of the Darjeeling Municipality is responsible for distributing water. The Public Health and Engineering Department (PHE) assists the Municipality with the supply systems. The PHE is the bulk water supplier for river-lifting projects and is also responsible for connecting the supply and distribution tanks. Spread across 10.75 square kilometres, the residents of Darjeeling receive their water from the municipality, community springs and private water suppliers (Chakraborty 2018). The household coverage of the municipality water supply is low —only 10-15% — with low supply frequency and volume (Samanta and Koner 2016; Shah and Badiger 2018). The remaining 80-85% do not have access to the Municipality’s water distribution system and are dependent on community springs and a variety of private water suppliers (Chhetri and Tamang 2019). This study focuses only on the formal water supply to examine its low and uneven coverage.

Formal Institutional and Governance Structure

The presence of a territorial administration introduces an additional layer to the three-tiered governance system that exists elsewhere in India. The Darjeeling hill district is one of the two hill districts under the jurisdiction of the Gorkha Territorial Administration – II (GTA-II). The territorial administration was first established in 1988, following violent protests demanding a separate state within the Indian nation. Political upheavals for a separate state occurred again in 2011 and 2017, which led to the formation of the Gorkha Territorial Administration (GTA) in 2011 and GTA-II in 2017 (Sharma 2014). This resulted in the split of the Public Health and Engineering Department (PHE) into two entities: State PHE, governed by the provincial authorities, and GTA PHE, managed by a territorial government. The PHE Department is highly specialised in technical skills and is responsible for extensive infrastructure projects and water transfer initiatives. The three departments – the State PHE, the GTA PHE, and the Darjeeling Municipality – make up the formal water provisioning system.

A lack of cooperation between the three agencies has been affecting the water schemes under development. Since independence, the Indian and West Bengal governments have proposed and approved 13 projects of varying sizes, costs, and purposes for Darjeeling town. Of these, only five are fully operational, with one functioning at half capacity (Shah 2023). The lack of coordination between the PHE and the municipality was evident when a 1,00,000-gallon storage tank built by the PHE in 1981-83 never received water (Rasaily 2014).i The PHE cited a lack of support from the Darjeeling Municipalityii – the latter was supposed to fill the water tanks and use the water. While both these departments are under the Government of West Bengal, their differences were not resolved, leading to the abandonment of the project - such issues highlight the presence of multiple institutions and fragmented governance (Rasaily 2014).

These projects have also essentially been adding more water to the supply system without upgrading the distribution lines (Shah 2023). Institutional and technological barriers often make ‘adding more’ the most common solution, despite the lack of significant or comprehensive studies, as these approaches are aimed at meeting immediate needs (Brown et al. 2011). Among the considerations water planners must account for, the most attention is given to increasing the number of sources, while very little is given to the distribution process and user demands (Anand 2001).

There are numerous cases in India where freshwater is imported from up to 100km away, despite local water sources and infrastructure being neglected by state authorities (Lele et al. 2019). Only in 2016 did the AMRUT 1.0 project under the municipality become the first to focus on the restructuring of distribution tanks and pipelines, in contrast to earlier projects, which focused solely on adding new sources to the water system (Municipal Affairs Department Government of West Bengal 2017). This project was intended to support the Balasun River Scheme, a river-lifting scheme under the State PHE to increase the supply sanctioned in 2004-2005. Both the AMRUT and the Balasun River Scheme projects were aimed at addressing the town’s water issues.

New initiatives for water supply and urban development that focus on adding more sources fail to address issues caused by institutional fragmentation and overlapping authorities and responsibilities. In their haste to tackle these problems, planners overlook locally-developed water management strategies and self-management techniques. Policy-driven approaches may neither provide water to socioeconomically disadvantaged groups nor sufficiently expand centralised formal systems. This was evident from a Water Works Department official, who stated that AMRUT 1.0 primarily aims to improve distribution infrastructure, indicating no effort or plan to understand or address the challenges communities face in obtaining connections. Consequently, the project risks merely enlarging existing gaps, benefiting only the top 10% who are already connected (Samanta and Koner 2016).

Structural Obstacles Faced by Households

Legal restrictions stop tenants and slum residents from applying for water or electricity connections directly. Slum residents can obtain a temporary number that allows access to electricity but cannot apply for municipal water. Slum settlements spread across 24 wards overlap with the BPL population. Hence, the legal deterrents and financial restraints push them out of the eligibility criteria to obtain a municipality connection.

Tenants require a No Objection Certificate (NOC) from landlords to request a water connection. In hill areas, no rental property guarantees continuous running water. Landlords often rent out homes without providing running water. The tenant demographic primarily includes young college students or households with young parents and children seeking education. They often visit springs, dropping their jerry cans there or at public taps every morning before college, and collect them on the way back. Those living nearby sometimes take their weekly laundry home.

Households receive 1,500 litres of water weekly, with the supply lasting 60 to 80 minutes. The sporadic supply worsens households’ problems when pipelines are disrupted, as they receive no prior warning. It is only when they do not receive water at the scheduled time that they realise their pipeline is broken. They miss out on one water cycle and must identify and repair the disruption in time for the next supply round. Since the municipality’s supply and maintenance take time, households often attempt repairs themselves. First, they need to locate the disruption and fix it before losing another supply. All this occurs while their homes have no water. The challenges of accessing irregular, inconsistent, and difficult maintenance further discourage people from applying for a municipal connection.

Municipal public taps serve as the primary municipal sources in slum areas, as private connections are often unaffordable and inaccessible for these communities. These public taps are situated in open spaces and are used by 18% of households at no cost (Shah 2023). The town’s upper reaches, which coincide with the town centre, receive regular water supplies from the municipality, including a few public taps that operate 24 hours a day. The number of dependents is inversely proportional to the water share. In the Darjeeling municipality, public taps follow the same supply schedule as private taps. When multiple households rely on public taps—which is most often the case—their turn may not come for up to 15 days, leaving them to wait for the water they need.

In some areas, house ownership also determines who can access the public taps, as houseowners around the tap set the rules. The older residents claim they have spent time and money acquiring the taps; hence, they have the right to block any other user. This puts the tenants in a limbo with no access to either private or public municipal water sources. They are left to find their own water supplies. Interestingly, there are also cases of disappearing public taps in some wards of the town, where powerful houses in the neighbourhood have subsumed them. In one ward, they mentioned that public taps “come and go with the municipality ward commissioners”.

Although ideal for many households due to their zero costs and open access, public taps can become inaccessible due to the nature of house ownership and their limited supply, supply schedules, and the number of households dependent on them provide only a bare minimum. Publicly-managed water is provided differentially, often focusing on their return on investment of communities (Hellberg 2014). Further, the presence of a public source implies that the water is a shared resource, leaving them with lower water endowments than those with individual water connections. Living in a slum or an informal settlement compounds the difficulty of accessing basic services. Despite being notified, the Darjeeling slums lack water and sanitation facilities. Some have been able to obtain municipal supplies by leveraging socio-economic power, social networks, or their status as municipal employees.

In addition to the difficulties in applying for municipal connections, public perceptions of municipal water supplies are adversely affected by their infrequency, irregularity, and limited availability. As a result, many do not attempt to connect. With the high application fees, legal documents, long waiting times (Shah and Badiger 2018) and the need to have someone within the municipality “to move your papers” (Anand 2011), a municipality private individual connection in Darjeeling has become something of a luxury. It has moved from being a basic necessity with universal access to a status symbol that only a few with the financial, legal, and social capacities can acquire.

Spatiality Determines Access

As a colonial town, Darjeeling initially served as a sanatorium, which was segregated by design. These included the colonisers living in the upper town and the natives living in the lower town. This segregation allowed private individual connections to the upper town of British households and only public taps to the native households.

The formal water supply system today reflects these historical management and investment practices (Bakker et al. 2008). The segregation and exclusion which began during colonial times are still propagated in terms of the settlement of the incoming population and the lack of resources (Ganguly-Scrase and Scrase 2015; Giordano et al. 2002; Alankar 2013). The incoming population is tucked away at the town’s farthest and lower fringes, in areas the municipality never reaches.

Continuing segregation is evident from the concentration of the municipality’s sources in the town centre. The central location of the municipality’s water supply system and of administrative centres define a household’s position in obtaining a connection (Shah 2024). The upper town centre had the highest proportion of municipal connections (66%), highlighting the concentration of water suppliers closer to the town centre and indicating spatial segregation of sources; some of the public taps here have a 24-hour water supply. The remaining 34% is divided between the town’s northern and southern parts. In the mountains, altitude is also a driver – the farther below from the upper town, the fewer connectivity options.

The spatiality created in colonial times is reflected in the absence of municipal water supplies in areas outside of the town centre and in informal settlements. An examination of the types of water connections the municipality provides highlights spatial segregation within the town and at the household level. Furthermore, home ownership is a driver of access not only to private but also to public water systems, often excluding the tenants. This uneven distribution worsens when private suppliers enter the scene, aiming to supply water to paying customers, thus transforming water from a public good into a commodity. This underscores the importance of broadening the focus beyond formal water provisioning institutions to include community-based water setups and private water suppliers, which have been filling the large gap left by the municipality.

Conclusion

The structures and functioning of governance hinder effective water governance. Where multiple departments govern the same resource, there are different forms of fragmentation, such as political fragmentation, issue-based fragmentation, mismatches between biophysical and political boundaries, and gaps in design and implementation (Shah and Badiger 2018). This has led to, on the one hand, ineffective project implementation and, on the other, the inability to self-assess and innovate (Kiparsky et al. 2013). Most of the time, the focus has been on technological solutions that prioritise bringing water to people and adding more sources, without considering aspects such as last-mile connectivity and user demands. At the household level, their location is an important indicator of access – upper or lower town, formal or informal settlement, and new entrant or old resident.

Water scarcity has been seen as something which needs to be planned, developed, and conserved, focusing on engineering and management solutions (Mehta et al. 2011; Mosse 2008). Innovation in technology and institutions is essential because socio-cultural and behavioural factors, equity, and institutional frameworks underpin effective water management (C Singh et al. 2020). The focus should be on improving distribution infrastructure and strengthening institutional functions to enhance access, with support from political and executive bodies. The aim of increasing the state’s water supply coverage needs to consider households and the legal and financial obstacles to obtaining a municipal connection. The municipal water connection, despite its high connection fee, has the lowest water fee among paid water suppliers. There needs to be a push for the formal institutions and governance framework to consider them as priorities going forward.

ENDNOTES

- Interviews taken with PHE contractors and Municipality officials in 2018-19

- Interviews taken with PHE contractors and Municipality officials in 2018-19

REFERENCES

Alankar. 2013. “Socio-Spatial Situatedness and Access to Water.” Economic and Political Weekly 48 (41): 46–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/4416969

Anand, Nikhil. 2011. PRESSURE: The PoliTechnics of Water Supply in Mumbai. 26 (4): 542–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2011.01111.x

Anand, P. B. 2001. Water ‘Scarcity’ in Chennai, India: Institutions, Entitlements and Aspects of Inequality in Access. UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER)

Bakker, Karen, Michelle Kooy, Nur Endah Shofiani, and Ernst Jan Martijn. 2008. “Governance Failure: Rethinking the Institutional Dimensions of Urban Water Supply to Poor Households.” World Development 36 (10): 1891–915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.09.01

Bhutia, Sherap. 2017. “A Situational Analysis of Water Resources in Darjeeling Municipal Town: Issues and Challenges.” International Journal of Research in Geography 3 (4): 52–60.

Castan Broto, Vanesa, Adriana Allen, and Elizabeth Rapoport. 2012. “Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Urban Metabolism.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 16 (6): 851–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00556.x

Chakraborty, Anup Shekhar. 2018. “‘Hamro Jhora, Hamro Pani’ (Our Spring, Our Water): Water and the Politics of Appropriation of ‘Commons’ in Darjeeling Town, India.” Hydro Nepal 22: 16–24.

Chhetri, Ashish, and Lakpa Tamang. 2019. “Decentralization of Water Resource Management: Issues and Perspectives Involving Private and Community Initiatives in Darjeeling Town, West Bengal.” Annals of the National Association of Geographers India 39 (2): 240–55. https://doi.org/10.32381/atnagi.2019.39.02.6

Domenech, Laia, Hug March, and David Sauri. 2013. “Contesting Large-Scale Water Supply Projects at Both Ends of the Pipe in Kathmandu and Melamchi Valleys, Nepal.” Geoforum 47: 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.02.002

Fareedi, Mashqura, and Pasang Dorjee Lepcha. 2002. Area and Issue Profile of Darjeeling. DLR Prerna.

Ganguly-Scrase, Ruchira, and Timothy J. Scrase. 2015. “Darjeeling Re-Made: The Cultural Politics of Charm and Heritage.” South Asia: Journal of South Asia Studies 38 (2): 246–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2015.1031203

Giordano, Meredith, Mark Giordano, and Aaron Wolf. 2002. “The Geography of Water Conflict and Cooperation: Internal Pressures and International Manifestations.” The Geographical Journal 168 (4): 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0016-7398.2002.00057.x

Hellberg, Sofie. 2014. “Water, Life and Politics: Exploring the Contested Case of eThekwini Municipality through a Governmentality Lens.” Geoforum 56: 226–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.02.004

Joshi, Deepa. 2014. “Feminist Solidarity? Women’s Engagement in Politics and the Implications for Water Management in the Darjeeling Himalaya.” Mountain Research and Development 34 (3): 243–54. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-13-00097.1

Kiparsky, Michael, David L Sedlak, Barton H Thompson, and Bernhard Truffer. 2013. “The Innovation Deficit in Urban Water: The Need for an Integrated Perspective on Institutions, Organizations, and Technology.” Environmental Engineering Science 30 (8): 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2012.0427

Lama, Arpan, and Nima Doma Lama. 2025. “A Spatial Assessment of Water Scarcity Using the Water Poverty Index in Darjeeling Municipality, West Bengal, India.” World Water Policy, August 26, wwp2.70026. https://doi.org/10.1002/wwp2.70026

Larkin, Brian. 2013. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (1): 327–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522

Meehan, Katie M. 2014. “Tool-Power: Water Infrastructure as Wellsprings of State Power.” Geoforum 57: 215–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.08.005

Mehta, Lyla, Nicholas Xenos, Betsy Hartmann, et al. 2011. The Limits to Scarcity: Contesting the Politics of Allocation. Edited by Lyla Mehta. Orient Blackswan Private Limited.

Millington, Nate. 2018. “Producing Water Scarcity in São Paulo, Brazil: The 2014-2015 Water Crisis and the Binding Politics of Infrastructure.” Political Geography 65: 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.04.007

Mosse, David. 2008. “Epilogue: The Cultural Politics of Water - A Comparative Perspective.” Journal of Southern African Studies 34 (4): 939–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070802456847

Mukherjee, Jenia, and Gorky Chakraborty. 2016. “Commons vs Commodity: Urban Environmentalisms and the Transforming Tale of the East Kolkata Wetlands.” Urbanities 6 (2): 78–91.

Municipal Affairs Department Government of West Bengal. 2017. “AMRUT State Annual Action Plan.” State Mission Directorate, AMRUT, West Bengal.

Narain, Vishal, and Aditya Kumar Singh. 2019. “Replacement or Displacement? Periurbanisation and Changing Water Access in the Kumaon Himalaya, India.” Land Use Policy 82: 130–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.12.004

Rai, Maheema. 2015. “Health Security of Women Labourers Living in Slums: A Case Study of Darjeeling Town.” Sikkim University. http://14.139.206.50:8080/jspui/handle/1/3120

Ranganathan, Malini. 2015. “Storm Drains as Assemblages: The Political Ecology of Flood Risk in Post-Colonial Bangalore.” Antipode 47 (5): 1300–1320. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12149

Rasaily, D.S. 2014. Darjeeling Pahadka Nagarpalika Kshetra Ko Vikas Ra Khane Paani Ko Itihaas Sanchipta Ma, San. 1835-2012. New Delhi.

Samanta, Gopa, and Kaberi Koner. 2016. “Urban Political Ecology of Water in Darjeeling, India.” SAWAS Journal 5 (3): 42–57.

Shah, Rinan. 2023. “Disentangling the Drivers of Domestic Water Scarcity in the Eastern Himalayan Region.” Manipal Academy of Higher Education. https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8443/jspui/handle/10603/490694

Shah, Rinan. 2024. “Ways of Storing and Using Water: Experiences of Uneven Water Scarcity in a Water-Rich Region.” Grassroots - Journal of Political Ecology 31 (1): 831–46. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5436

Shah, Rinan, and Shrinivas Badiger. 2018. “Conundrum or Paradox : Deconstructing the Spurious Case of Water Scarcity in the Himalayan Region through an Institutional Economics Narrative.” Water Policy 22 (S1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2018.115

Sharma, Gopal. 2014. “GORKHALAND – Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC) to Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA) - What Next?” Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies 2 (6): 44–50.

Sultana, Farhana. 2013. “Water, Technology, and Development: Transformations of Development Technonatures in Changing Waterscapes.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 31 (2): 337–53. https://doi.org/10.1068/d20010

About the Author : Dr Rinan Shah is a former Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Centre for Himalayan Studies, Shiv Nadar University, Delhi-NCR. Her work engages with the question of thinking/rethinking water governance in the mountainous landscapes in a rapidly urbanizing world with uncertain and intense ecological calamities. Her PhD thesis attempted to disentangle the drivers of domestic water scarcity in the volumetrically “water-rich” Eastern Himalayan Region. She can be reached at her email id [email protected].

Share this on: